In the middle of the twentieth century, scientific laboratories in the United States were not neutral spaces and access was very limited. For a Black woman, the path into advanced scientific research was neither open nor encouraged. Overcoming the dual hurdles of racial and gender bias, Marie Maynard Daly entered that world anyway.

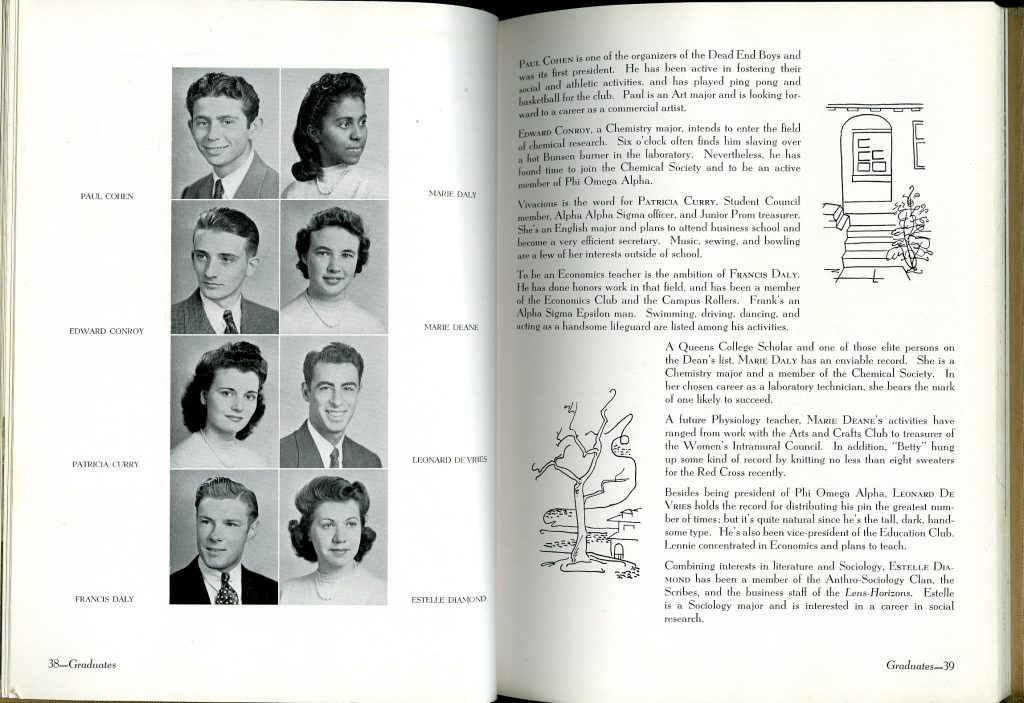

She first moved through classrooms that were more open than most. At Hunter College High School, an all-women’s school that admitted students on merit, her teachers encouraged her ambition to become a chemist. She went on to Queens College in Flushing, New York, which offered free tuition to local students. Queens College, like other universities, was adapting to the wartime environment. During World War II, around 1,200 of its students joined the U.S. military, creating new opportunities for women and minorities.

Daly trained as a biochemist, earned her PhD in chemistry in 1947, and began investigating how the chemistry of blood, pressure, and diet shapes the health of the heart.

Courtesy Queens College

| Quick Fact:

In the 1942 Queens College Silhouette yearbook, Daly appears in the top-right photograph on the page. She is the only Black graduate shown there, even though many of the other students pictured are women. The short note beside her name highlights her strong academic record and mentions that she hopes to work as a laboratory technician. When you read her profile next to that of Edward Conroy, the other chemistry major on the page, it’s useful to look closely at the language used for each. Which qualities are emphasised? What similarities and differences do you observe? Something to think about. |

The Breakthrough

In the 1950s, science hadn’t fully figured out that heart attacks are not sudden incidents but they come with warning. Marie Maynard Daly set out to map what was really happening inside the body long before a crisis struck.

At Columbia and later at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, she began investigating how cholesterol and blood pressure damage blood vessels over time. She designed experiments using animal models, isolating the effects of high-fat diets and hypertension on the circulatory system. The results showed how arteries narrowed, pressure climbed and fat deposits grew. The data made it clear: this wasn’t just a sudden calamity but a factor of chemistry with consequences.

Her work revealed a relationship that now seems obvious, that diet and blood pressure are active forces that shape the heart’s future. And she showed it at a time when cardiovascular disease was still treated as a conundrum.

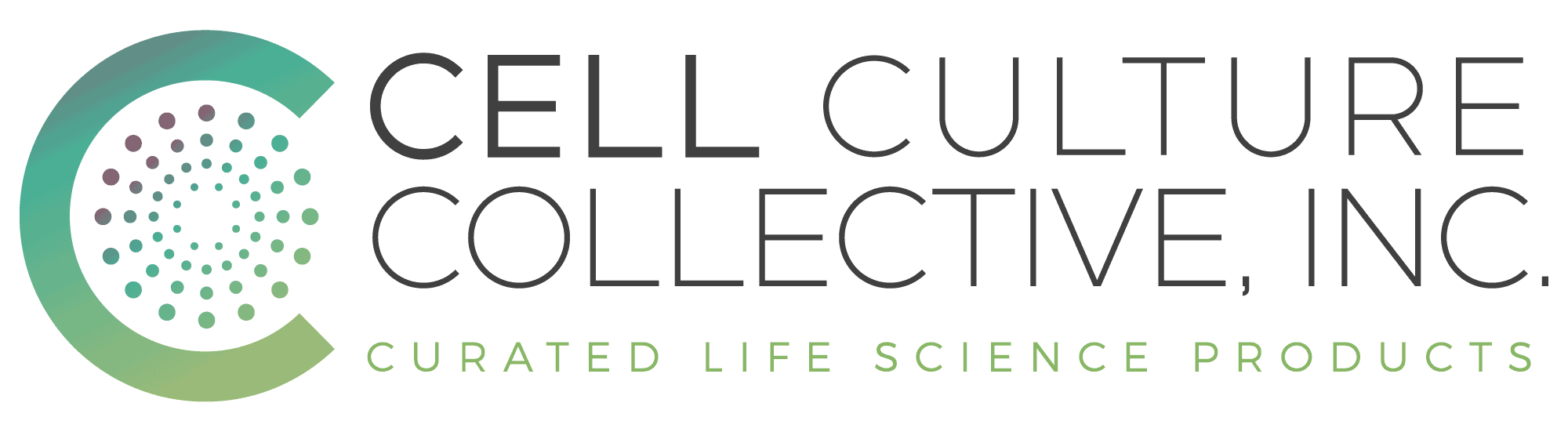

Marie Maynard Daly working in her lab, ca. 1960.

(Archives of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Ted Burrows, photographer)

Why It Matters Today

Cardiovascular disease remains the world’s leading cause of death. It killed an estimated 19.8 million people in 2022, which equals about 32% of global deaths. In the United States, heart disease still leads all causes of death, with 680,981 deaths reported in the CDC’s leading-causes table.

Marie Maynard Daly made this crisis measurable long before prevention became mainstream. She studied how cholesterol and diet change arteries over time, and she investigated how hypertension accelerates vascular damage. She understood that heart attacks are not random events. She treated them as the end of a biological process that science could track, quantify, and interrupt.

Modern cardiovascular prevention still rests on the same risk factors her work helped clarify. The American Heart Association lists cholesterol and blood pressure control as core components of cardiovascular health, alongside diet, physical activity, tobacco avoidance, and blood sugar management. Major clinical guidelines also treat elevated LDL cholesterol and high blood pressure as central drivers of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk, and they recommend therapies and lifestyle changes around them.

That is Daly’s lasting impact. She helped move heart disease from uncertainty to mechanism, and from mechanism to prevention.

Why Now?

- February marks American Heart Month, a national campaign led by the NIH (NHLBI) and American Heart Association to raise awareness about cardiovascular disease, the world’s leading cause of death. The focus is on prevention: lifestyle changes, early detection, and long-term risk management.

- Marie Maynard Daly’s research is foundational to this conversation. In the 1950s and 60s, she conducted some of the earliest controlled studies showing how high cholesterol diets and elevated blood pressure contribute to vascular damage. Her data helped prove that these were primary drivers of disease.

- Her work predicted the shift from reactive treatment to proactive care. Daly was among the first to treat heart attacks as the culmination of preventable processes inside the body. That insight continues to shape how researchers model disease progression and how doctors screen for risk.

- Featuring Daly this month grounds Heart Health Month in real science. A Black woman working in biochemistry at a time when no one was allowed into the field, Daly helped build the evidence that made this month necessary. Her research turned invisible, long-term cardiovascular damage into measurable warning signs and gave medicine a clearer way to understand risk before crisis. Prevention emerged because scientists like Daly proved what was happening inside the body, one experiment at a time.

The Standard She Set

It has always been harder for women in science. For women of colour, it has never just been about doing the work, it’s been about gaining access to do it at all. That was Marie Maynard Daly’s first obstacle, and it was no small one. Before she ever investigated a molecule, she had to break through a structure that wasn’t built for her.

She wasn’t just the first to discover something, she was the first to be allowed in the room and still chose to change the field.

We speak her name during Heart Health Month not just because of what she found, but because of what it took for her to find it. And because somewhere, another young woman, maybe the only one in the room, is studying, building the kind of work that will one day change what medicine thinks it knows.