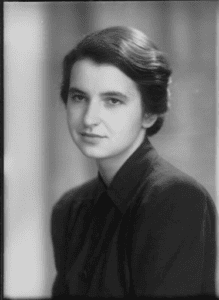

Long before the double helix became a symbol of modern biology, its shape remained an enigma. Scientists suspected DNA held the key to life’s code, but its structure was still out of reach. In a lab at King’s College London, Rosalind Franklin began a line of experiments that would change that.

With a background in physical chemistry and an exceptional command of X-ray diffraction, Franklin set out to capture DNA in sharper detail. Her experiments produced some of the clearest images of the molecule’s structure, offering concrete data when the field needed more than theory.

Today, the impact of her methods and the integrity of her science continue to shape how researchers understand biology at its most fundamental level.

Rosalind Franklin by Elliott and Fry. Credit: © National Portrait Gallery, London

The Breakthrough

In 1951, Rosalind Franklin joined the Medical Research Council’s Biophysics Unit at King’s College London, where she was tasked with applying X-ray diffraction to DNA fibres. She brought with her technical expertise, and a level of experimental discipline that would eventually reshape the field.

One of her most important contributions was identifying that DNA existed in two structural forms: a more hydrated B-form and a dehydrated A-form. Franklin understood that each form revealed different features under X-ray, and she worked methodically to capture clear diffraction patterns under precisely controlled humidity conditions. This insight would prove essential. It allowed her to isolate the B-form; the version that eventually revealed DNA’s now-famous helical geometry.

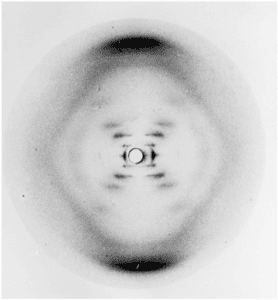

Working with her graduate student Raymond Gosling, Franklin captured an exceptionally sharp diffraction image of the B-form in May 1952. Known as Photo 51, the image displayed a clear X-shaped pattern that strongly suggested a helix.

Photo 51. Credit: King’s College London

But its real value came from what it allowed scientists to measure. Franklin’s interpretation provided key parameters: the dimensions of the helix, the number of units per turn, and the spacing between them. These were facts derived from data she had spent months perfecting.

Her findings were published in Nature in 1953, alongside two other papers: one by Watson and Crick presenting their model of DNA, and another by Maurice Wilkins’s group. Franklin’s paper presented experimental evidence, it formed the backbone that validated the model. Her measurements made the structure plausible. Her methods made it real.

Why It Matters Today

The tools of molecular biology have advanced dramatically since the 1950s, but the principles behind them remain rooted in structure. Many researchers today rely on diffraction, imaging, and atomic-resolution techniques to understand the architecture of DNA, RNA, and proteins, the same kind of methods Rosalind Franklin refined in her time.

Her work showed that scientific progress actually begins with clear data. The distinction she made between A and B forms of DNA is still fundamental in crystallography and structural biology. It reminds scientists that molecules behave differently under different conditions, and that those conditions must be understood before conclusions are drawn.

Rosalind Franklin’s lab at Birkbeck College. Credit: @JohnFinch/MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology

Franklin’s legacy also lives on in the way modern research values rigour. Structural biology, genomics, virology each of these fields depends on accurate models built from carefully captured evidence. Techniques like cryo-electron microscopy and synchrotron-based X-ray imaging may be more powerful today, but they follow the same logic that shaped Franklin’s experiments: control the variables, observe with precision, and let the structure reveal itself.

In an era where technology moves quickly and answers are expected instantly, Franklin’s approach remains a fundamental standard. Her insistence on disciplined inquiry continues to influence how scientists ask questions, interpret results, and build knowledge that lasts.

Why Now?

January resets the rhythm of research.

Projects resume and teams regroup. Experiments are revisited with fresh intent. It’s a time when scientists return to their benches to work carefully to refine protocols, recalibrate instruments, and chase clarity over speed.

That mindset aligns closely with how Rosalind Franklin approached science.

Her X-ray diffraction studies on DNA were not quick and theoretical. She spent a long time improving sample conditions, adjusting humidity levels, and repeating measurements until the data spoke clearly. Her most famous image, Photo 51, was the result of controlled variables and deliberate choices, the kind of work that thrives at the start of a new cycle.

Honouring Franklin in January is a nod to the discipline behind discovery. As the year begins, her story reminds us that precision is a mindset worth returning to.

What Endures

Rosalind Franklin changed the course of science. She produced the data that made DNA’s structure visible. She interpreted it with precision and published it without overreach.

She set a benchmark for what scientific integrity looks like. While some raced to model DNA, she made sure the evidence was sound. While credit was indeed due, her results remained. Today, her papers are still cited. Her methods are still taught. Her name is no longer missing from the story.

To honour Franklin is to honorhow science should be done: with discipline, with skill, and with conviction. She didn’t just support a discovery. She built the foundation beneath it.

That foundation still stands.